Mooting for learning: interim report

Interim report from the UKCLE funded Mooting for learning project led by Alisdair Gillespie (De Montfort University) and Gary Watt (University of Warwick), presenting the findings from phases I and II of the project.

Phase I results

Phase I comprised an overview of undergraduate mooting in UK law schools. Having identified the key academic staff member with responsibility for mooting in each law school we invited them to tell us about mooting at their institution. In particular we wanted to discover whether their students engage in mooting, and, if they do, whether they do so on an intra- or extra- curricular basis. Institutions with intra-curricular mooting were asked to inform us whether mooting forms part of the students’ diet of assessment, and, if so, whether it is summatively assessed (ie contributes to the students’ overall course grades) or formatively assessed (ie does not contribute to overall course grades).

A total of 85 questionnaires were sent out to institutions offering an undergraduate law programme. All areas of the UK were represented, as the project focuses on the use of mooting and not the content of the curriculum. Accordingly jurisdictional issues are not considered to be relevant.

A total of 58 (69%) of questionnaires were returned. The only area of the UK not represented in the responses was Northern Ireland. For the purposes of our analysis we have distinguished between ‘pre-1992’ and ‘post-1992’ institutions.

| Responses | N(T=58) | % |

| pre-1992 institutions | 24 | 41 |

| post-1992 institutions | 34 | 59 |

The number of responses from post-1992 institutions and pre-1992 institutions were in a broad ratio of 3 to 2.

Use of mooting

Phase I invited institutions to describe their particular use of mooting, if any. Institutions were permitted to tick more than one box (ie they could indicate that intra-curricular mooting is assessed or not assessed as appropriate), but if, for example, an institution reported that it engaged in both intra- and extra- curricular mooting that institution was categorised as an institution engaging in intra-curricular mooting. Likewise, if an institution reported that it engaged in both assessed and non-assessed intra-curricular mooting, that institution was categorised as an institution engaging in assessed intra-curricular mooting. In short, institutions were categorised to reflect positively the proximity of their mooting activity to teaching, learning and assessment within their law degree course.

The results were as follows:

| Use of mooting | N(T=58) | % |

| do not moot | 4 | 7 |

| purely extra-curricular | 22 | 38 |

| intra-curricular but not assessed | 5 | 9 |

| intra-curricular and assessed | 27 | 46 |

It can be seen immediately that a majority of institutions reported that they operate mooting as an intra-curricular activity (58%), but that 39% of institutions continued to operate mooting as an extra-curricular activity. Some form of mooting operates in 93% of institutions, with only 7% of institutions indicating that their students do not moot in any form.

Ten year movement

Phase I revealed a general trend toward intra-curricular mooting during the ten years since the Warwick survey.

| Ten year movement | 1995 | 2005 |

| extra-curricular moots only | 80% | 41% |

| intra-curricular moots | 20% | 59% |

(Those institutions not mooting are excluded from results)

Expressed as a ratio it can be seen that the change in the use of mooting throughout the last ten years has been dramatic. In 1995 the ratio between intra and extra-curricula moots was 1:4, and yet by 2005 this had changed to 3:2. This demonstrates a significant change in the undergraduate curricula in a relatively short period of time. It is intended to explore the reasons for this change during phase III of the project.

Where is the intra-curricula mooting happening?

The initial analysis demonstrated a sizeable shift, but could our analysis inform us where intra-curricular mooting is being used?

| Intra-curricula mooting | N(T=32) | % |

| pre-1992 institutions | 10 | 31 |

| post-1992 institutions | 22 | 65 |

This demonstrates that twice as many post-1992 institutions use intra-curricular mooting as pre-1992 institutions. This is perhaps evidence of the widely held perception that post-1992 institutions are prepared to be more flexible in their assessment strategies. The 10 pre-1992 institutions that use intra-curricular mooting account for almost one third of all pre-1992 respondents. The 22 post-1992 institutions account for just over two thirds of all post-1992 respondents.

We also wanted to examine when students experience intra-curricular mooting – the results here were quite definitive.

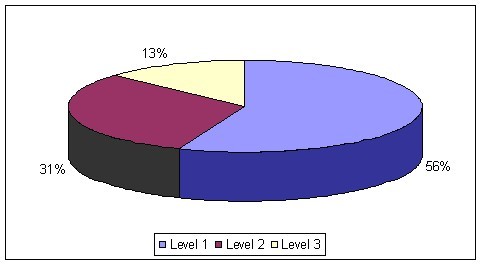

Level at which intra-curricular mooting takes place

It can be seen that the majority of intra-curricular mooting takes place in the first year of the undergraduate programme. Approximately one third of all intra-curricular mooting takes place during the second year – only 13% takes place during the final year of a student’s study.

It is intended to examine the reasons why mooting takes place predominantly in the first year during phase III, but our analysis of the modules during which a moot takes place indicates that the first year is deliberately chosen, probably because it inculcates certain skills early in the curriculum. This is borne out by the nature of the modules in which mooting is used, as demonstrated by the following diagram:

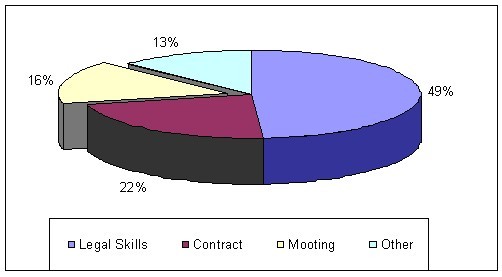

Module in which mooting takes place

It can be seen that ‘Legal Skills’ (a term we have used to encompass a number of different module titles all collectively dealing with the skills required for the study of law) is the major ‘home’ for intra-curricular mooting. Perhaps this is unsurprising, given that mooting is perceived to be a ‘skill’, but we might have expected to see the use of mooting as a form of teaching or assessment in ‘substantive modules’.

The second most common form of mooting takes place in the Law of Contract – again, a common first year module. Phase III will examine whether this is because the institutions ‘embed’ legal skills in substantive law modules rather than provide discrete modules.

A discrete module purely in mooting was used in only 16% of institutions. Interestingly, it does not appear that this is an area of particular change. In the 1995 study undertaken by the Warwick law students only five institutions offered a discrete module in mooting, the same number found in our study. It would appear, therefore, that although mooting has moved itself into the curriculum in the past ten years it has not been recognised as a form of learning and teaching in its own right. Interestingly, the most recent survey of law schools (Harris & Beinart in The Law Teacher 39(3)) identified six institutions that offered a dedicated mooting module (the difference in numbers perhaps being reflected in response rates), and so the pattern remains similar throughout surveys.

The use of mooting as a discrete module will be examined during phase III of this project.

Phase II results

Phase II targeted those institutions which indicated that mooting takes place within their curricula. Two questionnaires were sent out – the first to institutions which assess mooting summatively and the second to institutions that do not. The latter category comprises institutions which do not assess mooting at all and those which assess mooting, but only formatively.

The questionnaires examined the use of mooting at module level. They asked a number of questions surrounding the use of mooting in the curriculum, including the number of students who moot, the weight of the module, the aims and objectives of the module and the advantages and disadvantages of using a moot in the module. The results of phase II are still being analysed, but it is possible to identify certain initial trends and issues.

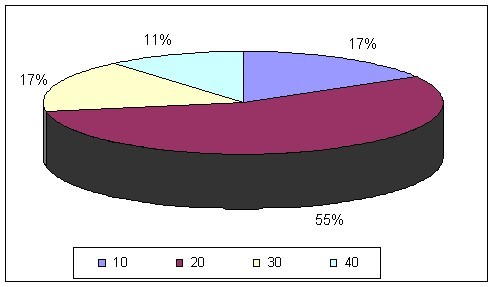

The first question we wanted to examine was the CATS weighting of modules in which mooting is used (ie how many CATS credits (or equivalent) do the relevant modules attract?). Each institution appears to have a different system of credits (for example base 12, base 10, base 20) so we used a scale whereby ranges were used – up to 10 credits, up to 20 credits, etc. The results demonstrated that the vast majority of modules were worth 20 credits, a ‘typical’ single or half year module.

Number of credits awarded for mooting module

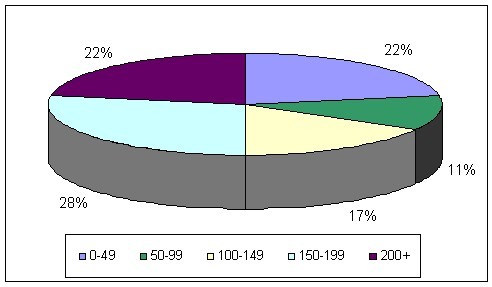

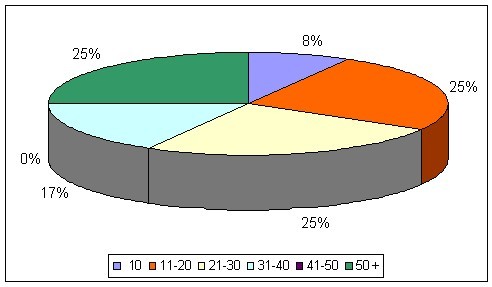

We then examined how many students undertake the moots. There is a perception that any presentation, but particularly a moot, is a lengthy process, so we were keen to identify whether mooting is used only in modules taken by small numbers of students. The results indicated this was not the case.

Number of students undertaking mooting

We have grouped the student numbers in bands of 50 for ease of reference. Whilst there appears to be a more or less even spread between categories, the 150-199 band is clearly the biggest. If we label anything over 100 students as ‘large’ then it can be seen that 67% of the modules contained a ‘large’ number of students, thus demonstrating that student numbers do not seem to deter the use of mooting within the curriculum. This will be explored in greater depth during phase III.

We were also interested to discover how many times students moot during the relevant module, especially in light of the findings that mooting was used in modules that had large class sizes.

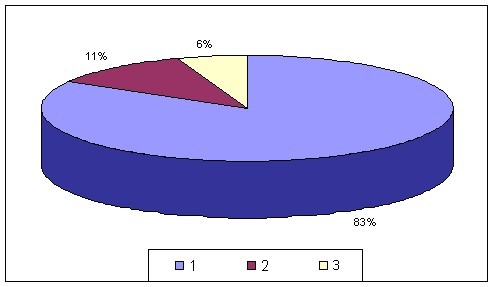

Number of moots undertaken

It can be seen that in the vast majority of institutions there is only a single moot within the curriculum, although a number of institutions reported that where the moot is assessed they encourage students to moot in an extra-curricular manner prior to the intra-curricular moot. Multiple moots appeared to be highly exceptional, restricted to those situations where the module was a discrete module in mooting.

Assessment

The initial results of phase II did not differentiate between modules in which the moot is assessed and those in which it is not. However, where the moot was used as part of an assessment we wanted to discover what weight the assessed moot carries. This question was restricted solely to those institutions which indicated that they use moots as part of the summative assessment process.

The results (next diagram) demonstrate that the results were fairly equivocal, but that the most popular grouping is between 10 and 30% of the overall assessment weight for the module. Where the module is assessed 100% by moot, this was in a discrete mooting module, but invariably a number of elements (not merely the oral performance) contributed to the assessment grade. Not every institution explained what those elements were. This will be explored during phase III.

Assessment weight for mooting as percentage of overall assessment for module

Advantages

Phase II also asked module leaders to identify advantages in using mooting within the module. Whilst a whole series of individual reasons were advanced, the four most commonly cited were that it developed:

- Communication skills (mentioned by 45% of respondents).

- Research skills (mentioned by 55% of respondents).

- Critical thinking skills (mentioned by 30% of respondents).

- Team working skills (mentioned by 20% of respondents).

It is interesting that the four most cited reasons are skills-based, but not limited to simple presentation skills, and it is notable that the second and third most popular responses were the development of research and critical thinking skills. These issues will be teased out further during phase III.

The challenges that mooting presents were also examined. The four most cited issues here were:

- Staff workload (mentioned by 60% of respondents).

- Scared students (mentioned by 25% of respondents).

- Student absence (mentioned by 35% of respondents).

- Consistency of marking (mentioned by 20% of respondents).

Given the number of students using mooting within the curriculum it is perhaps unsurprising that staff workload is perceived to be the number one issue. It is interesting that quality is effectively only raised at issue 4, consistency of marking, and this is something that we wish to consider in more detail during phase III. Interestingly, because the vast majority of mooting takes place at level 1, the requirement to produce a format suitable for external examiners has been avoided. Where mooting occurs in the higher levels there is a variety of strategies adopted to allow external examiners to reflect upon the work, the most usual being either the production of written work or the recording of moots (either audio or audio-visual).

Student absence is obviously problematic, since mooting is relatively methodical. If, for instance, the junior appellant is not present it makes it more difficult for the junior respondent to perform his or her role. This could have an impact on performance and quality.

Last Modified: 6 July 2010

Comments

There are no comments at this time